Book Review: The Math Academy Way

Memorization is just knowing things

Sorry, July, I just don’t think we had good chemistry. It wasn’t me; it was you. You were just too hot for me to handle…or too humid.

Anyway, it’s August, and I’m back on the horse. Here’s a book review.

The Math Academy Way

I read through the public working draft of The Math Academy Way by Justin Skycak (his twitter), the creator of online math learning program Math Academy. I’m no longer a student and not yet a parent, but I socialize with many people involved in alternative education and this came across my feed.

Math Academy is in the business of teaching math, but The Math Academy Way explains the why and how of learning that is transferable to other domains, which is why I read it and you might enjoy it. For examples other than math the book (paper?) uses frequent analogies to sports talent development, and here is a twitter thread applying the knowledge graph part of the method to learning to paint.

There’s lots of information that will help you learn to learn, but in my opinion the most important part of the Way is its discussion of “automaticity.” If you believe Skycak about automaticity, a positive view of memorization follows. The first part of this essay explains what automaticity is and why it’s good in general, not just for math. Then I write about a second key topic, the knowledge graph, and how you can apply that to your own learning project. I follow with some miscellaneous tips from the book that you can apply to your own studies of whatever.

Portions of the book cover topics specific to schooling, like grade inflation. I’ve omitted those topics from this post because they aren’t relevant to me, but if you’re an educator who has been living under a rock, you may want to read those parts.

Automaticity and Memorization

Skycak says automaticity is “the ability to execute low-level skills without having to devote conscious effort towards them. Automaticity is necessary because it frees up limited working memory.” We all recall asking our teacher why we have to memorize our times tables. Figuring out 6*7 from scratch soaks up a lot of working memory that you need to do more complex operations. If you’ve got it memorized, all of your brain power can go to learning something new. This is part of why memorization is good, actually.

A digression on reading

Phonics has gotten a lot of attention in the last few years. You may have heard reporting about the controversy that schools were teaching kids to read using “whole word”/”whole language” curriculum instead of phonics based curriculum. Phonics (teaching letter sounds and directing children to sound out words) seems to be more effective than “whole word” curriculum (skipping phonics and aiming for sight reading by directing children to use context clues to recognize words on sight) or “whole language” (exposing children to lots of appropriate books without direct instructions and letting them pick it up like speaking, through exposure.)

In a Dick and Jane book, the idea was not for children to sound out the words. The idea was for them to see the same words over and over again and memorize them — store words kind of like pictures in their mind.

Now phonics is popular and fashionable in certain circles (as it should be, imho). However, the people who espoused whole word or whole language did recognize something true: proficient adult readers don’t sound out every word when they read; they read words on sight. They recognize words automatically.

This can lead to funny errors when it comes time to speak aloud a word learned through reading. When I read the Harry Potter books as a child, I didn’t sound out “poltergeist,” but I did add it to my vocabulary. I could recognize the word and understood that “Peeves the Poltergeist” was a mischievous ghost, but when I tried to speak in a sentence, I didn’t know exactly what letters were involved or what order they were in and therefore I couldn’t say it out loud. The whole word/language people are correct that knowing a word and spelling a word are two different skills.

But they are related skills. When phonics is known it becomes automatic, and sight reading is built on top of that. Proficient readers recognize words on sight so their working memory is allocated only to understanding. You can imagine how difficult it would be to understand the meaning of a complex text if you were also using a lot of brainpower to recognize words. Let’s simulate lacking this automaticity in reading by reading a sentence printed right-to-left and answering a question about it (left-to-right translation in footnotes):

.esav eht nekorb t'ndah maiL taht yas t'ndid airaM1

Question: Do we know for certain whether Liam broke the vase?

It’s not a very complex sentence, it’s just got a nested clause, but how difficult was it to grok its meaning?

You can read it, but it wasn’t automatic like normal reading is. If the pre-requisite reading is not automatic and a lot of your brain power is going to decoding the words, you have less brain power to use to understand the meaning of the sentence. You also have to hold everything you decode in your memory, because you can’t immediately understand it printed on your screen. It would be difficult to be creative and write something with this weak foundation.

Back to Math

Sight reading is automaticity applied to reading, like how, if you memorized your times tables, you just know the answer to simple multiplications without doing any mental arithmetic. That’s why you should memorize your times tables. Yes, you can decode a sentence written from right to left letter by letter. Yes, you can re-derive 7*6 by figuring 7*5=35, add another 6, carry the 1… but without automaticity, you won’t ever understand Charles Dickens or do calc.

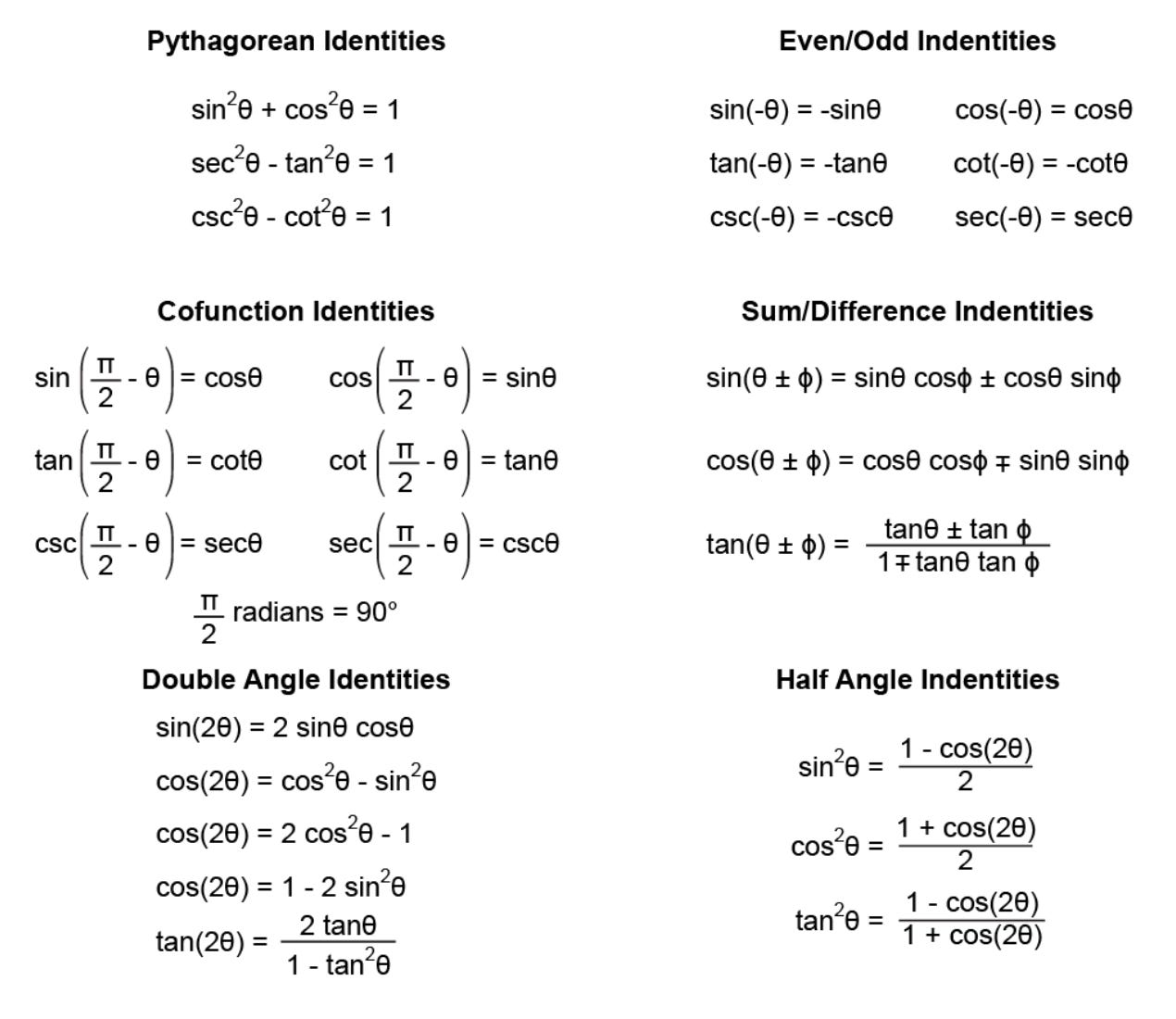

When I was learning trigonometry, we were presented with trigonometric identities to memorize. I never did.

I thought, “I have a deep understanding of trig, and so if faced with e.g. sin(-θ), I can visualize the triangle in my head and realize that it’s equal to -sinθ. I will re-derive these identities from scratch during a test.” But it never really worked out that way. This is the trig equivalent to decoding a sentence letter by letter on the fly. It takes a lot of memory and brain power, and you can’t spot these patterns in a problem if you don’t know the identities. I always felt it was unfair when a solution relied on a double angle identity “trick.” My virtuous and pure, unmemorized knowledge didn’t seem to be sufficient during the exam2.

Memorization is just knowing things.

“You don’t need to memorize, because you have the entire corpus of human knowledge available via google.” But you can’t build with potential bricks. You have more ingredients available to you at the grocery store than anyone in history, but you can only cook with what’s in your house. You can’t be creative, synthesize things, make connections, without the requisite knowledge. Recall the sweet satisfaction of spotting a reference in a book; you can’t make that connection if you aren’t familiar and comfortable with the referenced text.

I wish my teachers had explained automaticity the way that Skycak does, and valorized memorization instead of denigrating it.

The Knowledge Graph

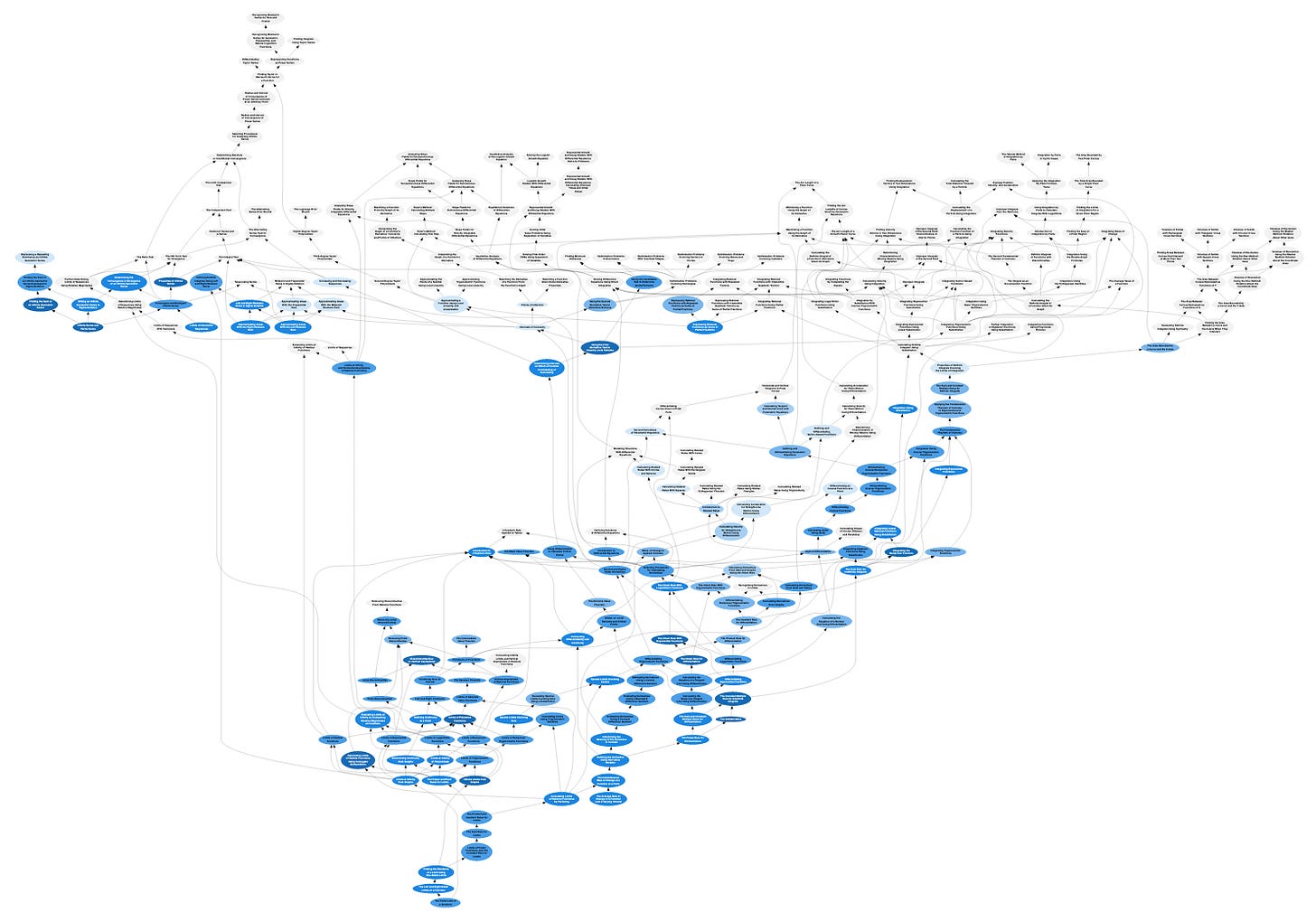

The Math Academy Way introduces another useful concept: the knowledge graph. It’s quite intuitive that one must know requisite skills to perform a complex skill, that lacking automaticity and confidence with requisite skill makes complex operations frustrating, and that missing those requisite skills makes complex operations impossible. Math Academy has created a map that graphs what math skills are foundational to other skills. For example, in order learn to subtract fractions with unlike denominators, you should be able to add fractions with like denominators.

Of course, if you demonstrate competence in subtracting fractions with unlike denominators, we can assume you are also competent to add fractions to like denominators. This scales from small steps like the graph above to very large scales like saying that calculus demands competence in algebra.

The Math Academy Way of teaching is to provide a very tight scaffold with small steps when students are first introduced to a skill and gradually remove it when practicing so the student does more on their own and must use recall. If a student is unable to come to the correct answer, [either the student is lacking in care for execution or] requisite skills are not understood. The Math Academy software knows the skills that make up each type of question and can find problem areas and target reviews of that material.

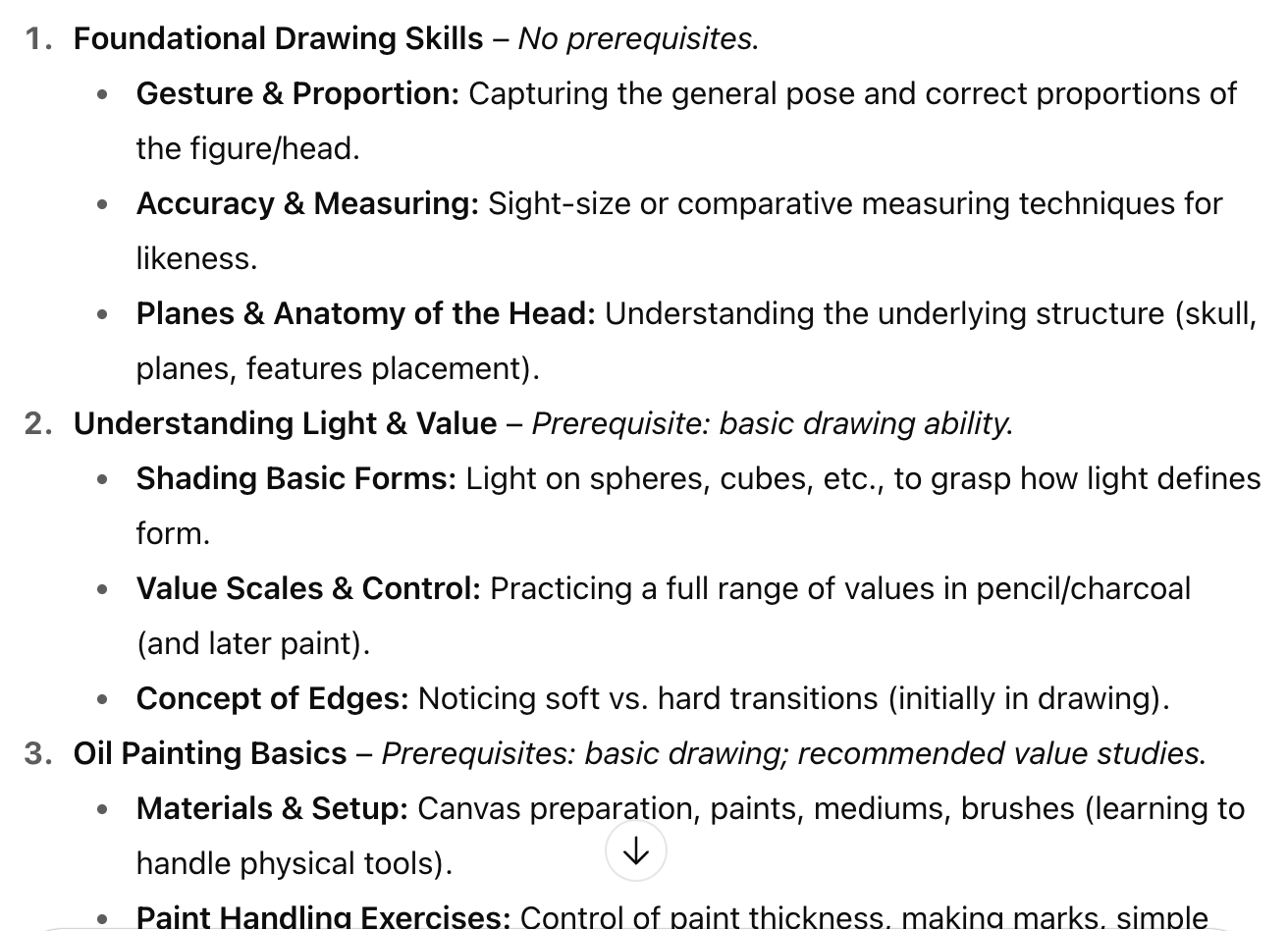

It’s with the example of the aspiring portrait artist that we see the broad value of this approach:

“So I’ve discovered that in order to paint portraits in oil, one must first understand portraits and oil paint; wow, genius! Thanks for writing this book review!” But consider it backwards: if your paintings look bad, it could be because the colors are bad, or the figures are bad. If your colors are bad, it could be because you don’t understand hue, or you don’t understand value. Having a detailed knowledge graph gives you a scaffold of skills to practice as you progress forward and a map to look backwards on when troubleshooting.

As an exercise, take some time to make a knowledge graph of something you’d like to learn. It’s like a skill tree in video game, but in real life!

If I want to be a pro soccer player who scores goals, I need to have good positioning, shooting, touch, and speed. Shooting and speed both require good dribbling. Dribbling and touch require good ball control. Etc, etc.

If I am struggling to understand a text in Greek, it could be that the concepts are going over my head, but it could also be that I lack automaticity with reading because I don’t understand the grammar, or I can’t read words automatically because I don’t recognize letter forms.

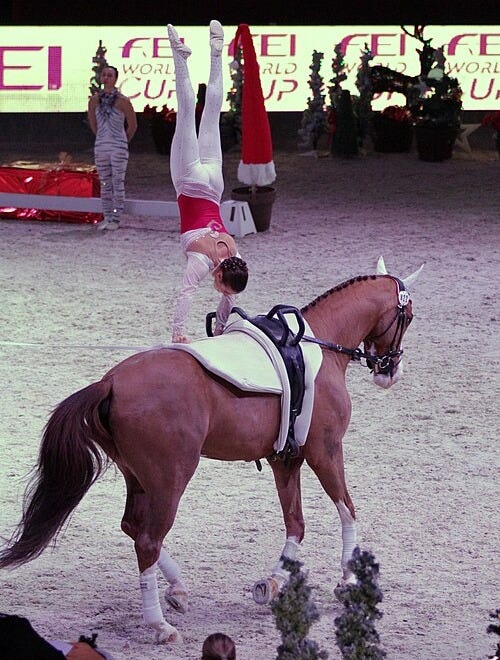

If I want to do horseback acrobatics at the circus, I need to be able to do a handstand on horseback. To do a handstand on horseback, I need to be able to do a handstand, so first I’ll try to learn a forearm stand… and I need to be able to ride a horse, which has it’s own skill tree.

Italian equestrian Anna Cavallaro, via wikimedia commons

Millions of man hours have been spent pretending to learn things by watching youtube videos. If you draft a knowledge graph, you can make yourself a road map towards actual ability. A scaffolded approach focuses practice hours on discrete skills of appropriate difficulty given your current competences and helps you evaluate your progress.

Methods You Can Use

Sprinkled throughout the book is other wisdom:

Spaced repetition—or rather, spaced recall—is the most effective way to review something. If you study only in one big long session, your knowledge decays quickly. Re-reading notes doesn’t make you recall something, so it’s ineffective. (In fact, Math Academy doesn’t seem to endorse students making notes at all.) Testing, by contrast, does make you recall by making you use your knowledge without guardrails, so test frequently and don’t use memory aids like notes unless you are stuck.

“Test anxiety” or any other excuse for test performance to be significantly worse than performance during practice is basically cope for not really knowing the thing you are testing for. To the extent that it does exist, you should recreate the test format and context often during practice.

One-on-one instruction is far and away the most effective. In a normal classroom, teachers don’t know who knows what, so students uncomfortable with pre-requisites are left behind and students ready to advance are held back. Nor are teachers able to tailor practice of specific concepts to specific students with an optimal period for spaced repetition. Math Academy does this through software; you can do it with Anki, a knowledge graph, and self testing.

Direct instruction with small intermediate steps is more effective than project based or discovery learning for beginners, but this reverses when you are an expert; take away the scaffold once you have the competence to be creative.

Learning takes effort; if your practice is too easy it probably isn’t effective. Pedagogical methods that feel hard to students are most effective, and methods that students enjoy are least effective.

Learning styles are fake, which hopefully you already knew. Some people are smarter than others, but [math] instruction is so poor that students aren’t in danger of hitting their ceiling. Take your talent development more seriously than you are.

Conclusion

Math Academy, as a software for learning math, seems great. I did some online math learning in high school, and it sucked. Being online made it even more terrible than my other (good) public school math classes, which were boring, slow, and not one-on-one. $49/student/month (as of summer 2025) seems absolutely fantastic for something that can take you from adding fractions through linear algebra. I wish such a thing existed 20 years ago. To the extent that The Math Academy Way is a sales pitch for parents and adult learners to purchase Math Academy, I’m sold. Check back in a few years when I have kids. I wish their company a lot of success.

To the extent that the book informs the reader about pedagogy in general, which is more relevant to me, I found it very good. As I hopefully made clear, what works for learning math works for learning. It’s a quick read, with okay density, decent diagrams, and lots of citations (if you care about that sort of thing.) The advice is actionable. My time reading it was well spent.

“Maria didn’t say that Liam hadn’t broken the vase.”

I don’t want to give readers the wrong impression; I did get As in all my high school math classes and 5s on both AP math exams I took despite my weak recall of trigonometric identities. But I bitterly disliked math class and never used anything past algebra in my professional life.

I really loved this! Thank you for writing it

thanks for writing this review! i thought it was careful, densely informational, and easy to read.